Wolfsdorf Immigration Blog

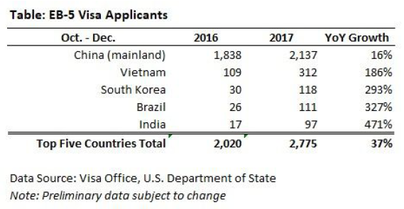

We previously blogged about the growing demand for EB-5 visas from Vietnam in October 2017. Now, recent analysis from the U.S. Department of State (“DOS”) and from IIUSA, confirms this reality. IIUSA recently indicated:

| The EB-5 visa usage for Vietnamese applicants jumped 190% year-over-year from October to December 2017. Since almost half of the annual EB-5 visa allocations for Vietnam (approximately 700) has already been used in the first quarter of the current fiscal year, the Visa Office predicts that Vietnam will face oversubscription by April [2018], at which time a Final Action Date will be required. After this happens, Vietnamese EB-5 visa applicants will subject to the same FAD [Final Action Date] established for Chinese EB-5 visa applicants for the rest of FY2018. |

The DOS has indicated in the February 2018 Visa Bulletin that the Vietnam EB-5 category “will become subject to a Final Action Date no later than April. The China-mainland born, and Vietnam employment fifth preference dates would be the same.” The China Final Action Date is currently July 22, 2014, meaning Chinese investors who filed before this date can get final green card interviews, or file to adjust status. Once Vietnam becomes subject to the same date as China, any of the demand for EB-5 visas from Vietnamese nationals that cannot be allocated for the remainder of the fiscal year (based on DOS’ predictions) will be held in “pending” status.

The annual limit for each country is only 7.0% of the EB-5 allocation of 9,940 or 696.8 visas. Therefore, each country has less than 700 visas available annually (for Vietnam and India this is only about 200-250 families). When one country uses all its available visas (like China for EB-5), applicants from those countries may be allocated unused visas available from the worldwide limit. Any excess EB-5 visas available to oversubscribed countries will be issued based on an investor’s priority date. Unfortunately, because there are so many Chinese investors with earlier priority dates, the Vietnamese will need to wait for those Chinese investors to clear first, or until the new annual limit becomes available at the beginning of FY 2019 (October 1, 2018).

However, unless an increase in the minimum investment amount slows demand, or Congress increases the number of EB-5 visas available, this problem will get exponentially worse as more Vietnamese investors file I-526 petitions. If this level of demand continues, Final Action Dates for Vietnamese EB-5 investors can be expected for the foreseeable future. The critical difference between the backlogged China quota and the Vietnam Final Action date is that demand from Vietnam isn’t as large, so that, when the new annual visa allocation becomes available at the beginning of FY 2019 (October 1, 2018), the Vietnam Final Action Date will likely be later than the Chinese one. Some good news is that the DOS has informally advised that based on current indications, all Vietnamese applicants with priority dates through the end of 2017 will likely be processed to conclusion within the next 4 ½-5 years.

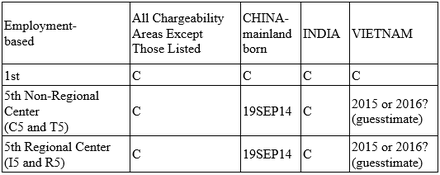

October 2018 (FY2019 Q1) Visa Bulletin Guesstimate

Chinese Final Action Date Guesstimate September 19, 2014

Vietnam Final Action Date Guesstimate 2015 or 2016 (most likely 2015)

Vietnamese investors with teenage children should learn from the Chinese EB-5 wait line. Unfortunately, derivative children stuck in a waiting line, where the visa number is not current at the time of approval, are unable to lock in their age under CSPA until their Final Action Date is “available”.

In addition to Vietnam, India has also seen a dramatic surge in EB-5 visa usage. EB-5 visa demand rose almost 500% from the first fiscal quarter of 2017 (October 1, 2016 – December 31, 2016) to the first fiscal quarter of 2018 (October 1, 2017 – December 31, 2017), proof that demand from India is skyrocketing. However, this 500% trajectory is already two years old and estimation of current I-526 filings is speculative. So, while India is very unlikely to use its annual visa quota in fiscal year 2019 (from October 2018-September 2019) according to unofficial State Department sources, we speculate that may change for fiscal year 2020, when India may also hit its annual quota, like Vietnam has now. Of course, this may not occur if there is a substantial increase in the minimum investment amount that slows demand, or Congress increases the number of EB-5 visas available

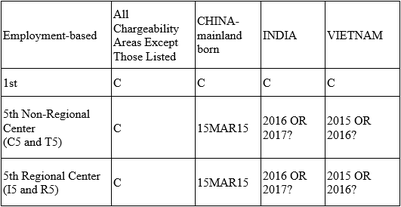

October 2020 Visa Bulletin Guesstimate

Chinese Final Action Date Guesstimate March 15, 2015

Vietnam Final Action Date Guesstimate 2016?

India Final Action Date Guesstimate 2016 or 2017?

South Korea or Brazil Guesstimate 2020 or 2021?

One way to guard against this is to file with the minor child as the principal applicant. Our office is now filing EB-5 applications for minor Chinese children as the principal investors using legal instruments such as UTMA, the Uniform Transfer to Minors Act and Chinese law. So far, the USCIS is open-mindedly approving these petitions. We have had approvals for children as young as 15 years old and will also be filing for children as young as 13 years old.

With almost 40,000 petitions filed in the last three fiscal years, representing about $20 billion in foreign capital investment, we can only anticipate increased waiting lines. Applicants chargeable to the “Big Five”, China, Vietnam, South Korea, Brazil and India are advised to plan years ahead. Unfortunately, there are too many variable factors to precisely determine each country’s waiting line. The variables include attrition through the 4D’s, denial, dropout, death, or divorce.

While we realize that the visa allocation system under the Immigration and Nationality Act is complicated, it is critical for potential and current EB-5 investors to understand the waiting line system to plan their immigration strategy. Regional Centers and EB-5 projects need this information to prepare for return of capital to new commercial enterprises and for the redeployment of funds in compliance with current USCIS policy guidance.

As the U.S. Congress contemplates immigration changes, it should correct the drafting error that occurred when enacting the EB-5 Visa via the Immigration Act of 1990. Clearly expecting to admit 10,000 investors annually, the drafters inadvertently counted both investors and their families against the annual limit. While for the first 27 years demand for this program has been low, this has now changed creating long waiting lines for Chinese applicants, and creating a shorter waiting line for Vietnamese applicants, and maybe even for Indians, South Koreans and Brazilians, in the near future unless we see changes to the program.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed